US Power Generating (USPG) entered into a definitive agreement and plan of merger with Tenaska Capital Management (TCM). Pursuant to the terms of the agreement, USPG will become a wholly-owned indirect subsidiary of TCM. Under the terms of the merger, TCM will purchase USPG, with the final price being determined by a number of business and tax adjustments. Consummation of the merger is subject to customary conditions including approvals of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission and the New York Public Service Commission.

US Power Generating to Merge with Tenaska Capital

Cross-Border Bargaining

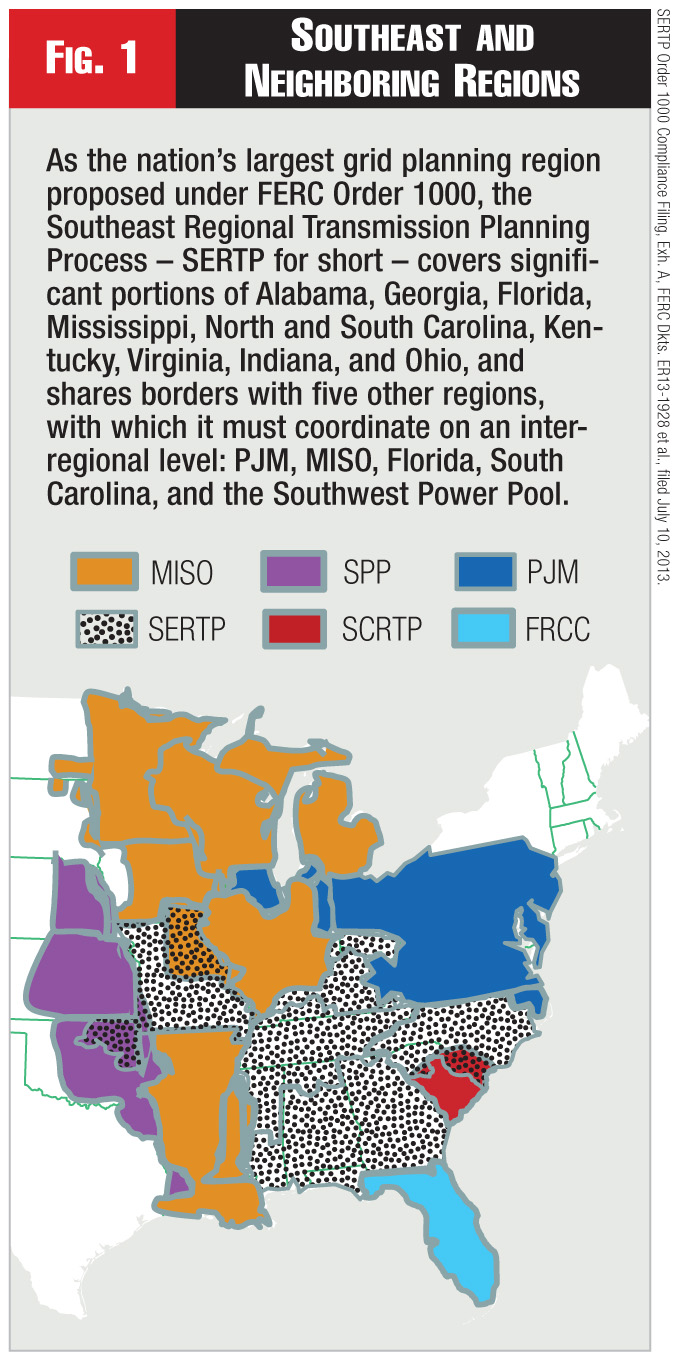

Interregional grid planning under FERC Order 1000.

Bruce W. Radford is publisher of Public Utilities Fortnightly. Contact him at radford@pur.com.

Now that the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission has ruled on the various protocols proposed by the nation’s major grid groups to comply with the commission’s highly controversial, landmark Order 1000 on regional transmission planning, let’s examine the other half of FERC’s vision: the mandate that each region also must coordinate with each of its neighbors to explore ideas for interregionalgrid projects – projects that might prove superior to those already approved at the regional level.

As we’ll see, interregional planning is proving no less contentious than the regional variety.

Order 1000 required all public utility transmission providers to band together in geographic areas to participate in regional planning to identify and study new grid projects to meet needs posed not just by reliability standards, but also by economics and public policy mandates such as renewable portfolio standards. It also required planners to select certain projects to have their costs allocated across the planning region according to a method to be defined as part of the regional plan, and to make sure that any transmission projects so selected can be built and owned by “non-incumbents” – i.e., developers other than the incumbent load-serving distribution utilities who historically have built and maintained the nation’s electric grid networks.

Now we turn to the interregional mandate. Here, the FERC order requires those same transmission providers who have formed the various grid planning regions to go further and coordinate and share data – one region with another – such that each pair of neighboring regions might work together, as instructed by FERC, to “identify and jointly evaluate interregional transmission facilities that may more efficiently or cost-effectively address the individual needs already identified in the first instance through their respective local and regional planning processes.”

As FERC required for regional plans under Order 1000, the interregional phase calls for regions to define a cost allocation method. This new interregional method will apportion between the two regional neighbors all the costs of any cross-border grid project approved through interregional coordination.

FERC’s mandate, however, will require more than just one cost allocation method per region. In fact, it will require multiple permutations: a separate consensus and agreement between each and every respective pair of adjoining regions. That means, for example, that the Southeast Region, including Southern Company, Duke, and TVA, must devise and put in place no less than five potentially different interregional cost allocation methods: one for each of its five regional neighbors, those being PJM, MISO, Florida, South Carolina, and the Southwest Power Pool.

To keep things simple, let’s focus on just three case examples of proposed agreements between three pairs of neighboring regions: PJM-MISO, MISO-SPP, and Southeast-SPP.

Thinly Veiled

In theory, interregional planning between PJM and the Midcontinent ISO (MISO), both certified by FERC as regional transmission organizations, ought to be fairly easy. After all, the two RTOs won FERC approval nearly a decade ago, back in 2004, for their bilateral Joint Operating Agreement, a deal that put in place just about all of the elements that FERC is requiring in Order 1000 for interregional compliance.

The PJM-MISO JOA specifies both (a) a bilateral process for the two RTOs to coordinate planning on cross-border projects, including tie-lines that span the seam dividing the two regions, and other projects located wholly within one RTO but built to serve a need arising in the other, and (b) a cost allocation method for projects approved under the JOA.

And in fact, PJM has proposed to FERC that the commission should accept the JOA provisions (with certain tweaks and amendments) as providing enough guidance and specificity on interregional coordination and cost allocation for PJM to comply with Order 1000. (See, FERC Dkt. ER13-1944, filed July 10, 2013).

Nevertheless, the two regions now find themselves at odds. Their disagreement stems largely from MISO’s recent internal decision, noted in a prior column (see, “First Refusers,” February 2013), to give up on any region-wide allocation of costs for grid projects that MISO calls baseline reliability projects, and instead to assign all BRP project costs to the MISO pricing zone where the BRP would be located.

This move by MISO, which FERC approved last spring at the same time that it ruled on MISO’s Order 1000 regional compliance (142 FERC ¶61,215, Mar. 22, 2013), was seen at the time by some as a ploy to preserve exclusive rights for its member transmission owners to build any and all grid projects dealing with reliability. The reason stems from FERC’s rule in Order 1000 barring any such preemptive “rights of first refusal.” It does so only for transmission projects selected in the regional plan for regional allocation – ROFRs would still be allowed for grid projects whose costs are allocated locally, as is now the case for MISO BRPs.

But there’s more. MISO also is telling FERC that the JOA won’t work for Order 1000 interregional compliance, as PJM claims.

MISO insists (and FERC rules would seem to confirm this) that its internal policy switch on cost allocation for reliability projects – abandoning any region-wide allocation for BRPs – makes it impossible for it to use the JOA with PJM to comply with the interregional half of FERC Order 1000, at least for cross-border BRPs.

FERC’s Order 1000 states that for a cross-border, interregional grid project to be eligible for interregional cost allocation, it first must have been selected for regional cost allocation in the regional plans of each of the two regions that put forward an interregional coordination – a requirement that MISO BRPs no longer meet.

Instead, MISO offers two new proposals for reliability projects: one for tie-line projects that physically connect one RTO with the other, and a second for projects built wholly within one RTO to serve a need arising in the other. Tie-line costs would be allocated based on RTO boundaries. Cost allocation for non-tie-line projects would be settled through negotiations between the constructing transmission owner and the non-constructing TO (the one that actually needs the project built), with the constructing TO entitled to cancel the project if the parties can’t agree. (FERC Dkt. ER13-1943, filed July 10, 2013.)

MISO’s alternative proposal has sparked all manner of protest, not only from MISO’s interregional partner PJM, but from utilities and regulators as well.

After all, the JOA specifies a much more precise regime of interregional cost allocation.

For economic projects, known as cross-border market-efficiency projects (CBMEPs), the JOA allocates costs between the two RTOs based their respective shares of project benefits (a 70/30 weighting of energy production cost savings and reductions in net payments assigned to load). MISO appears to support this cost allocation method for economic projects for interregional compliance.

But for baseline reliability projects (CBBRP) – where the JOA requires a violations-based DFAX (distribution factor) method, which reflects each region’s respective share of power flows on the constrained facility or facilities necessitating the upgrade – MISO believes it must seek another way.

And so MISO is suggesting – for reliability projects at least – that grid owners will negotiate on the fly. And if talks break down, the project just gets canceled.

PJM’s transmission owners decry such an idea, which they see as a bid by MISO to re-write the JOA unilaterally. The PJM RTO terms the MISO proposal “a step backwards.”

PJM notes that while FERC Order 1000 would grant final authority to RTOs on interregional planning and expansion, “MISO proposes to transfer the decision-making responsibilities … to the individual transmission owners across the RTO regions,” giving them “unfettered discretion to decide whether or not a single RTO project needed for reliability by another TO in a neighboring region will be constructed.”(Protest of PJM, p. 19, FERC Dkt. ER13-1945, filed Sept. 9, 2013.)

The Ohio Public Utilities Commission goes further, calling MISO’s proposal “a thinly veiled attempt to protect the ROFR of its transmission owners, to the detriment of PJM, PJM TOs, and borders states along the PJM-MISO seam.” (Comments, Ohio PUC, p. 5, FERC Dkt. ER13-1945, filed Sept. 9, 2013.)

The irony, however, is that the JOA has performed woefully as a mechanism for getting cross-border projects built.

Testifying recently in support of MISO’s proposal for interregional coordination with PJM, filed this past summer at FERC to comply with Order 1000, Jennifer Curran, MISO’s v.p. of transmission, let the truth out:

“To date,” said Curran, “no cross-border projects have been approved for cost allocation under the existing JOA provisions.”

Northern Indiana Public Service Co. concurs, noting that “a joint coordination plan where nothing gets built is not a joint coordination plan, but instead a joint discussion.”

For its part, MISO argues in its interregional compliance proposal (see p.34) as if the JOA was never going to be of much help anyway, such that MISO’s apparent step back from the JOA provisions for reliability projects shouldn’t be of much concern:

“This change,” writes MISO, “does not have any immediate or foreseeable impact on implementation of the MISO-PJM JOA.

“As explained by Ms. Curran, there has never been an identified CBBRP in the history of the JOA, nor is one currently under consideration.”

Skewing the Results

Negotiations between MISO and the Southwest Power Pool on protocols for interregional coordination and cost allocation have sparked many of the same arguments we saw with the MISO-PJM proposals. That’s because MISO’s elimination of any region-wide cost pass-along for reliability grid projects approved through its own internal regional planning process will create the same problems in crafting an agreement with SPP, as with its dealings with PJM.

But the really interesting wrinkle in the SPP-MISO discussions surrounds Entergy’s merger with ITC and its coming integration into MISO. The Entergy deal has soured both SPP and its member transmission owners, who have long fretted that power transfers between Entergy and MISO will impose invasive and unwanted loop flows across the SPP grid, without adequate compensation, forcing SPP TOs to subsidize the Entergy deal.

(Readers seeking to learn more about this loop flow issue should take a look at FERC Docket ER13-1864, in which the Southwest Power Pool has proposed certain revisions to its JOA with MISO regarding terms and conditions for “market-to-market” procedures, and where SPP transmission owners have questioned whether compensation for loop flows created by the Entergy integration should be dealt with under FERC’s “traditional” policy, which envisions a voluntary settlement between affected parties, or whether such loop flows should be treated as intentional flows, for which compensation should be paid pursuant to rates in filed tariffs.)

Now, however, with SPP and MISO filing interregional compliance plans under Order 1000, we see the loop flow issue morphing into an entirely new dimension.

Available space here doesn’t permit analysis of all the ramifications, but it appears that SPP’s transmission owners now fear that MISO might be seeking to gain greater control over design, construction, and ownership over the portion of any new interregional, cross-border grid lines located with SPP territory. And as the SPP TOs argue, MISO could achieve that simply by re-working the definition of project benefits included in the interregional cost allocation formula that will bind the two regions.

Consider the following: For interregional coordination with SPP under Order 1000, MISO proposes an interregional cost allocation method only for MEPs – economic projects. And while it proposes to allocate costs for any such cross-border MEPs based on the respective ratios of benefits accruing to each region, it wants to employ a benefit metric that reflects only the change in adjusted energy production costs (APC). It wouldn’t recognize benefits stemming from a change in net payments for energy by load. (See, FERC Dkt. ER13-1938, filed July 10, 2013.)

Thus, according to the SPP grid owners, this intended emphasis on production costs has a sneaky purpose. As the TOs explain, it has been widely predicted that the integration of Entergy into MISO will achieve production cost savings for the rest of MISO. And the more grid lines built across SPP territory that interconnect with MISO and boost its capacity to trade with Entergy, the greater those production cost savings presumably will be.

Now take a look at one of MISO’s proposals in its interregional compliance filing with SPP. According to one of MISO’s proposed revisions for its JOA with SPP – Section 9.7.1: “Interregional Project Construction and Ownership” – the entity entitled to “construct, implement, own, operate, maintain, repair, restore, and finance” a MISO-SPP interregional tie-line will be determined based on the proportion of benefits calculated for the project. (See, “MISO Transmittal Letter,” p. 17, FERC Dkt. ER13-1938, filed July 10, 2013.)

Thus, given the claimed northward predominant flow of production cost benefits from the Entergy integration, plus MISO’s proposal to limit recognition of cross-border project benefits to production costs only, the SPP grid owners fear what they call a “skewing” of results.

Here’s their argument:

“MISO’s asymmetrical eligibility proposal would give MISO the opportunity to build and control any type of facility on the SPP system… By limiting the type of benefit … MISO’s proposal may be skewing the results… [A]s has been documented elsewhere, integration of Entergy into MISO is predicted to achieve production cost savings for MISO. If new facilities across SPP would further those savings, MISO’s one-dimensional test, which would disregard the local reliability benefits of such a line, could give MISO an advantage in efforts to control a large portion of the new line…

“The SPP TOs recognize that transmission systems often overlap, and we are not making these observations out of some misplaced sense of territorial protectionism – just the opposite, in fact …

The criteria for determining eligibility for interregional status should be the same on both sides of the border, and the tests for benefits should include all recognized forms of benefits, not just those that may favor the growth of one RTO over the other.” (See, Comments of SPP TOs, pp. 5-6. FERC Dkts. ER13-1937, 1938, filed Sept. 9, 2013.)

As of September 25, neither MISO nor its transmission owners had appeared to respond to these charges on the record in either of the two FERC cases involving MISO-SPP interregional coordination under FERC Order 1000.

But the SPP RTO has filed its own objections to certain MISO proposals.

First, as did PJM, SPP opposes MISO’s plan to exclude reliability projects from any interregional coordination, planning, and cost allocation. With interregional coordination reserved only for economic projects, SPP complains that opportunities for cross-border collaboration will be restricted unreasonably.

One reason lies with MISO’s minimum voltage threshold of 345 kV that applies to MISO-approved cross-border MEPs (no more than 50 percent of project costs can be attributable to lower-voltage facilities). But according to SPP, 80 percent of its interconnections with MISO are at a voltage level less than 345 kV. (See Exh. SPP-4, Testimony of David Kelley, p.11, FERC Dkt. ER13-1937, filed July 10, 2013.)

Thus, as SPP explains, removing lower-voltage projects from consideration “may encourage a less cost-effective solution, as high-voltage projects are typically more expensive.” (See, SPP Comments, p.23, FERC Dkt. ER13-1938, filed Sept. 9, 2013.)

But SPP goes further. If interregional cost allocation is to be limited to economic MEP projects, as MISO proposes, the Arkansas-based RTO wants to add a benefit metric for allocating costs that will reflect and capture the avoided costs of any reliability projects that the economic project might possibly delay or displace.

In fact, SPP proposes at some later date to develop and propose still another benefit metric for cross-border economic projects that would capture any occasional benefits related to satisfying public policy requirements.

“Adjusted Production Cost,” as SPP notes, “is not an appropriate metric to quantify reliability or public policy benefits …

“Additionally transmission solutions needed to meet public policy requirements are not always economical.”

Worth the Cost?

The largest of the Order 1000 planning regions, the Southeastern Regional Transmission Planning Process (or SERTP for short), which includes Southern Company, Duke, and TVA, proposes a cost allocation method for cross-border projects – the avoided cost method – that FERC already has rejected at the regional level, both for South Carolina (Dkt. ER13-107, Apr. 18, 2013, 143 FERC ¶61,058), and in fact for the Southeast as well (Dkt. ER13-908, July 18, 2013, 144 FERC ¶61,054).

Yet the Southeast now has won agreement for this method at the interregional level from four of its five neighboring regions: PJM, MISO, Florida, and South Carolina. The Southwest Power Pool remains the only holdout.

The Southeast defends its avoided cost method as permissible for interregional cost allocation since in its view, the reasons given by FERC for killing it in regional plans (i.e., that avoided costs fail to capture economic or policy benefits) shouldn’t apply at the interregional level. That’s because FERC Order 1000 didn’t establish interregional coordination as a separate free-standing planning process, empowered to study economic and policy needs, but only as a sort of second set of eyes, to review the regional plan one more time.

In its proposal for compliance under the interregional phase of Order 1000, the Southeast explains why an avoided cost method should suffice:

“Utilizing an avoided [or] displaced cost allocation metric facilitates the comparison of the costs of an interregional project with a project(s) which has already been determined to provide benefits to the planning region.” (SERTP Interregional Compliance Filing, p. 12, FERC Dkts. ER13-1928, 1930, 1940 & 1941, filed July 10, 2013.)

In other words, in SERTP’s view, the regional plan assesses the value and merit of project benefits from meeting reliability, economic, or policy needs. After that, you simply look to see if you can capture those exact same benefits at the interregional level with a cheaper project.

MISO and PJM have acceded to an avoided-cost method at the interregional level. However, they have each proposed – and SERTP appears to have agreed – that they will continue to explore other cost allocation methods for interregional planning, to ask for FERC approval if such other method is deemed suitable by the Southeast.

And for the record, the SERTP at this writing hadn’t yet returned to FERC to file a new Order 1000 regional plan to substitute for the one (with the avoided cost method) that the commission rejected on July 18. So we don’t yet know how the Southeast eventually will design its new preferred benefit metrics and cost allocation method for Order 1000 compliance at the regional level. In fact, on September 20, SERTP asked the commission for an extension of time, to Jan. 14, 2014, to file its amended regional plan.

As hinted above, the Southwest Power Pool doesn’t share SERTP’s enthusiasm for the avoided cost allocation method. Instead, SPP wants stakeholders at the interregional level to be able to propose projects that will address needs not already considered or included in the regional plan. The Southeast takes umbrage, accusing SPP of wanting to introduce top-down grid planning at the interregional level, usurping its preference for bottom-up transmission planning centered on state-regulated integrated resource planning.

As it did when it filed its regional plan, the Southeast insists that a transmission plan should not drive grid construction: rather, that state-approved IRP findings should serve as data inputs that govern the trajectory of grid expansion.

And as part of its interregional compliance filing, SERTP re-submitted an affidavit taken several years ago from Bryan K. Hill, at that time a transmission planning manager for Southern Company, declaring that “any perceived lack of interregional facilities in the Southeast does not indicate a failure of the planning processes to analyze such facilities, but instead a failure of those facilities to be worth the cost.”

Category (Actual):

Department:

America’s Energy Future: So Who Are the Good Guys?

Not just ‘all of the above,’ but ‘how much of each?’

Harvey L. Reiter (hreiter@stinson.com) is a partner with Stinson Morrison Hecker LLP, and serves as executive articles editor for the Energy Law Journal.

For proponents of a clean energy economy, identifying the “good guys” is no easy task.

Teaching a course in energy law and regulation at Vermont Law School a few summers ago, this author posed several questions to students about their views on clean energy. The students, almost to a one, had chosen the school for its environmental law program and their personal interest in a green future. And they brought to the classroom their own conceptions about who the good guys are in the energy economy. They came away, one hopes, with the understanding that identifying the good guys can prove immensely complicated – even where the policy goal (to promote clean energy) seems unambiguous.

The students grappled with a number of questions. What did they think about the importance of energy from wind? From solar? What of conservation? Of energy efficiency? Energy storage technology? Aren’t efficiency, conservation and storage all as green as renewable energy? These were all good things to be promoted, they said. But do they compete with one another and, if so, are some worth subsidizing over others? Are any worth subsidizing? Their answers to these questions were more equivocal. And the class, conducted several years ago, didn’t even touch on the more recent fracking debate or the explosive growth in oil production in North Dakota or from tar sands in Canada. But if the class were taught today, the list of questions would logically grow. Is hydraulic fracturing safe? Will it reduce carbon emissions? Should we be promoting its use to replace coal in power plants or oil in motor vehicles? Will it retard or hasten the arrival of a clean energy economy? How will the availability of cheap natural gas for transportation affect the development of electric or hybrid vehicles? How important is North American energy independence? If oil is going to be consumed anyway, is it better to rely on domestic sources? Can they help make us greener in the long run or will they slow progress?

Regulators, law makers, environmentalists, consumer advocates and energy industry participants will be asked these and similar questions if they aren’t already posing the questions themselves. And if they are conscientious, they will struggle for answers.

What is Green Anyway?

The broad and even overwhelming scientific consensus states that manmade carbon emissions are accelerating global warming.1 But it isn’t just the climate change skeptics who have questioned the merits of the various strategies proposed to reduce the size of our global carbon footprint. As a society, we might well agree on the need to meet defined levels of CO2 reductions or the related goal of domestic energy independence,2 yet disagree – and vigorously – on how to get there.

Many states, for example, have chosen to adopt renewable portfolio standards (RPS). These rules can mandate a generation mix for utilities that must include certain percentages of identified renewable resources by a date certain.3 This strategy will have the effect of reducing carbon use to the extent renewable generation displaces generation that consumes more carbon.

Suppose, however, that some resources are considered more renewable than others. In California, local utilities must attain certain targets for renewable energy portfolios, but renewable generation located outside the state counts less – or not at all – toward those targets4 Similarly, the state has developed a “low carbon fuel standard” that applies to “any transportation fuel … sold, supplied or offered for sale in California,” but that measures carbon intensity by including the amount of carbon used to produce and transport the fuel to California.5 So, for example, a gallon of ethanol produced in Brazil would have a higher carbon intensity than an otherwise identical gallon produced in California. In both the RPS and carbon standard cases, the apparent goal isn’t simply to reduce carbon emissions, but to promote in-state development of renewable resources and the boost it might give to the local economy.

In certain other states, large-scale hydroelectric projects – both existing and new – don’t qualify at all as “renewable.” Yet hydroelectric power serves as the quintessential example of a physically renewable resource: it rains, the rain evaporates, the water vapor condenses, and the cycle starts all over again. Policymakers in some states, though, have decided that counting existing hydroelectric projects toward renewable energy targets would give an insufficient incentive to utilities to expand their use of renewable resources – particularly in areas with plentiful hydropower resources. The argument for disqualifying new large-scale hydro is more difficult. Smaller-scale renewable energy resources, even small-scale hydro, often can’t compete with far lower cost large-scale hydroelectric plants. And most of the potential for large-scale hydroelectric projects isn’t in the United States, but in Canada.6 So disqualifying these projects serves not simply to reduce carbon emissions, but to protect nascent, homegrown renewable energy producers. Who are the good guys in that debate?

Here’s a more fundamental question. Are renewable energy portfolio standards – even those that are neutral as between various types of renewable resources – the best way to reduce carbon emissions? Economists generally agree that the best way to reduce carbon emissions is to tax them.7 But the political terrain for a carbon tax is treacherous.8 Even in the most prosperous of times, it’s far easier to pursue a public policy goal through regulation or tax credits and deductions than through an actual tax.

Short of a carbon tax, some economists would argue there are other, more efficient ways to reduce the use of fossil fuels in the production of energy than through RPS.9 Holding utilities to a carbon output standard, for example, in lieu of a renewable portfolio standard, would allow utilities to reduce carbon use through means other than increasing deployment of certain renewable technologies. One means of limiting carbon output is through a cap-and-trade mechanism, such as that employed by the EPA for years to limit SO2 emissions. Under cap and trade, utilities would fall subject to emission limits; those utilities exceeding their emission limits could buy allowances from other utilities with a surplus to spare. Legislation that would adopt cap and trade died in Congress in 200810 but the EPA arguably has authority to establish a cap-and-trade regime by regulation.11

The president recently directed the EPA to establish carbon emission limits for existing power plants.12 But while it’s unclear whether the EPA would opt for a cap-and-trade approach, other means are available to implement carbon usage limits. Under a carbon use standard, utilities could promote greater energy conservation or greater use of energy efficiency technologies (such as LED lighting, superconductivity technologies to reduce line losses, etc.). Switching from coal to natural gas (retaining some reliance on new fossil-fueled generation) might also count toward meeting carbon use reduction targets. Improvements in efficiency and conservation might also serve. Many utilities have argued, however, that if they’re compensated based on their sales levels, they will have inadequate incentives to promote conservation and efficiency, as such measures would necessarily reduce their sales. Maximizing efficiencies, they maintain, will turn on whether the state regulators allow rate decoupling – mechanisms by which utilities are compensated both for the energy they sell and for achieving reductions in customer usage of electricity, particularly during peak periods.13 Decoupling can take a variety of forms. A number of state regulators have implemented policies permitting decoupling.14

This carbon output standard also would allow the utilities to devise the mix of renewable resources and other strategies that would reduce carbon use at the lowest cost. Does the flexibility and short term cost of this approach make proponents of a carbon output strategy the good guys? What if there was evidence that, given an increase in demand for renewable resources (which an RPS, by definition, produces), the cost curve for these resources would decline sharply and that an RPS would accelerate this development? Policymakers might then prefer to minimize reliance on gas-fired generation, even if it has a lower carbon impact than coal or oil. The accelerated development of lower-cost solar or wind resources, prompted by an RPS, might shorten the transition period from fossil-fired to carbon-free generation. Would opting for an RPS over a carbon output standard be a rational choice for policymakers in these circumstances?

Wind vs. Solar: Taking Sides?

Deciding what’s green and what isn’t is difficult enough. But deciding what will best promote clean energy may involve making choices even among similar green alternatives. Wind generation offers a case in point. Maryland recently passed legislation, long promoted by Governor O’Malley, to subsidize development of 200 MW of offshore wind capacity. Residential ratepayers will pay an additional $1.50 per month and businesses will pay a 1.5-percent surcharge per month.15 Will it promote the use of clean energy? Well, that depends.

Will the subsidy borne by ratepayers allow wind to develop even if solar is cheaper? If so, is that a green outcome? Will the cost of the legislation make it more difficult for legislators already facing budget constraints to call on ratepayers also to subsidize energy conservation or energy efficiency programs? If these programs are market-driven they will have to compete with wind resources. Could development of other, possibly more efficient green technologies be retarded as a result? Or will the wind subsidy serve to jumpstart offshore wind, increase economies of scale, lower costs and produce jobs in the long term, as the Governor hopes?16 How is this equation affected by the availability of low-cost natural gas produced from shale deposits? Will the subsidy be enough to achieve its intended result?

In passing the legislation, Maryland lawmakers are betting that the benefits of potential job creation and lower carbon usage will outweigh any a long-term detrimental consumer impact from higher rates. Lawmakers in other jurisdictions might reach different, but equally plausible conclusions. By asking the right questions, though, they improve the odds that they can reach clean energy goals without materially sacrificing efficiency.

Even like sources of renewable energy can compete with each other, posing still other difficult policy questions for regulators.

Several years ago wind project developers and others in the Great Plains argued, vociferously, for a federal rate-making policy that would favor large-scale transmission projects to move wind power to the Northwest and the Northeast. The idea was to spread the cost of these new lines across entire regions, among utilities and their customers. Socializing the costs in this way, they insisted, would be necessary to get the transmission built and to make the wind resources economic. But regulators, legislators and others in the destination regions balked. These projects, they complained, were uneconomic. Subsidizing them would come at the expense of competing offshore wind projects that were closer to load and wouldn’t require the same investment in long-distance transmission. Not only did the idea of socializing large wind-related transmission projects stall, it prompted some legislators to propose bills that would have barred transmission funding that wasn’t tied to proportionate consumer benefits.17 And while the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s Order No. 1000, issued in 2011, did ease the way somewhat for broad allocation of new grid project costs, the Order expressly precludes allocation of the costs of interregional transmission projects without the consent of each of the affected planning regions.18

Offshore wind projects face additional obstacles. Like onshore wind, they need subsidies to survive, particularly given the drop in natural gas prices.19 But they also face environmental objections from landowners, naturalists and fisherman, as was the case with the Cape Wind project off the shore of Cape Cod. And they’re difficult to construct. So-called “jack-up” ships are needed to transport and install offshore wind turbines but the U.S. doesn’t have any, although a New Jersey company, Weeks Marine, hopes to have its first in use by 2014.20 Still, it makes sense to pose the same questions when comparing offshore wind projects to other renewable, efficiency, and conservation alternatives, and when comparing such projects to more distant onshore wind projects.

Greens and Consumers: BFFs?

Just as the climate change debate can pit one technology against another, so too has it made adversaries of traditional allies, like environmentalists and consumer advocates. As environmentalists have championed wind power and the associated grid infrastructure, a number of environmental groups have come to favor transmission rate incentives for new transmission. Consumer advocates, meanwhile, have criticized FERC policies granting rate-of-return adders for new transmission as needlessly expensive rewards for doing what utilities were likely to do anyway and, in some cases for building transmission, they were already obligated by contract to construct.21 So who are the good guys in this skirmish? Consumer groups seem to be making headway in convincing environmentalists to look at costs and rates. A handful of environmental groups recently have joined consumer advocates in counseling FERC against heeding utility calls to make its rate-of-return policies more generous.22 Whether environmental groups will find common cause with consumer interests on the shale gas revolution is still an open question.

Shale Gas: Bridge to Nowhere?

Geologists and petroleum engineers have long known that shale formations, found throughout the United States and other parts of the world, hold large deposits of natural gas. But until the last decade and advances in the combined use of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing these deposits have been economically unrecoverable. The availability of inexpensive natural gas supplies from shale – between 2003 and 2012 prices per Btu fell from $20 to $3 – has dramatically changed the energy landscape. It has, for the most part, made new coal-fired electric generation uneconomic23 and if the price differential persists (oil is currently six times as expensive as natural gas),24 it’s also likely to encourage more fuel switching by homeowners and vehicle operators from fuel oil and gasoline to natural gas. Most significant in terms of carbon impact, burning natural gas produces about half the CO2 emissions of either oil or coal.

So what are the difficult questions consumer advocates, environmentalists, policy makers, regulators, and consumers should be asking about producing gas from shale? T. Boone Pickens has famously argued that moving from oil to natural gas for our transportation needs will provide a necessary bridge to a renewable-based energy system. Some environmental groups have warned that reliance on any fossil-fuel will instead prevent society from making the changes necessary to eliminate reliance on fossil fuels. Still others have warned that uncertainties about the safety of fracking – groundwater contamination, seismic disturbances, adequacy of water treatment facilities, warrant a halt to further development. Taking this view, the State of Vermont, which has only limited shale gas potential, enacted a moratorium on its development.

The answer likely lies somewhere in between abandoning this fuel source and a full-speed-ahead approach. MIT economist Henry Jacoby sees big advantages to the economy over the next few decades from shale gas. The 2012 report he coauthored projects it creating thousands of jobs, lowering energy prices and driving “conventional coal out of the system.”25“But,” he says, “it is so attractive that it threatens the other energy resources we ultimately will need.”26 For one thing, lower energy costs will boost energy consumption, “yielding more emissions than if shale remained uneconomic.”27 This effect won’t only make coal uneconomic, but it will make various forms of renewable energy and conservation efforts uneconomic as well. The MIT report estimates that, without other changes in policy, use of renewables to meet energy needs would never exceed RPS minimums as a result of the availability of natural gas from shale. And it would delay the date that carbon capture and storage would become economic for fifteen years. The good news, the report says, is that the lower energy costs from use of shale gas can help finance the transition to an energy economy not based on finite fossil fuels. And it offers this sage advice: Don’t let shale gas become a crutch instead of a bridge.

Pipelines or Trains?

To borrow a phrase from the pre-digital era, journalists, consultants and others have spilled a lot of ink addressing the merits and downsides of the Keystone XL Pipeline, a project to bring Canadian oil from tar sands to US refineries in Texas and Louisiana.28 The debate, if not the answer, is pretty straightforward.

Keystone proponents argue that thousands of jobs in the U.S. and Canada will be lost if the pipeline isn’t built. Denying a permit, they add, won’t reduce carbon emissions from this source of oil nor prevent environmental degradation around the exploration site; the oil will be produced anyway and will simply be sold by the Canadians on the world market through other ports.29 Canadian oil, they add, will reduce US reliance on energy from Venezuela and the Middle East.

Opponents, by contrast, have maintained that extraction and transportation of the oil will itself pose environmental hazards and that, in any event, our government shouldn’t be endorsing the export of oil from tar sands because bitumen oil from these sources produces more greenhouse gases and other adverse environmental impacts than conventional oil.30 Some voice concern that making this oil available domestically will slow expanded use of electric vehicles. Still others argue that the U.S. shouldn’t allow the transportation of oil, period. 31

Just as oil from Canadian tar sands promises to reduce U.S. reliance on oil imported from outside North America, so too have large oil finds in North Dakota made the US a potential exporter of fossil fuels.32 Lacking the pipeline capacity to market their North Dakota oil outside of the Great Plains and the Midwest, North Dakota oil producers have argued that the absence of a facility like Keystone is depressing the prices they receive because they can’t market their oil into the Southwest or Gulf coast states, where prices are higher.33 This is the same concern voiced by Canadian bitumen oil producers.

Nearly lost in the Keystone controversy are two other developing phenomena – the increased use of rail transportation to move Canadian and North Dakota oil and the largely undiscussed development of a competing oil pipeline network by Enbridge and their combined potential impact on the environmental debate. These developments promise to render the Keystone debate – but not other environmental debates – irrelevant.

Over the last five years, rail carriers in the U.S. and Canada have greatly expanded their capacity to handle crude oil shipments. They do this by adding rail cars and running them more frequently, not by adding new tracks. The Railway Association of Canada has estimated that its members will ship up to 140,000 carloads of crude oil this year – compared to only 500 carloads in 2009.34 U.S. shipments of oil by rail have jumped just as dramatically, from 9,500 carloads in 2008 to 233,811 carloads in 2012.35

The significance of expanded rail shipments of oil is this: oil can and is being moved using existing rights of way. So issues such as wetland disturbances, stream crossings (the Keystone pipeline involve over 200 such crossings), scenic impacts and pipeline safety associated with citing new pipeline facilities, as well as the delays in obtaining governmental permission to operate new pipeline facilities, aren’t factors.

All this is not to say that shipments of crude by rail pose no safety or environmental risks of their own. Oil spills from pipelines or offshore facilities can have widespread catastrophic consequences, like those resulting from BP’s offshore disaster in April 2010 or the Enbridge oil spill into the Kalamazoo River the same year. Spills from rail cars are more frequent– twice as frequent says the American Action Forum. Still, because oil is stored in individual tank cars, the overall damage is usually less severe. But that isn’t always the case. A recent rail car derailment in Quebec, for example, killed 40 people, spilled oil from over 70 tanker cars and forced 2000 people from their homes in the small town of Lac-Megantic – “the fourth freight train accident in Canada under investigation involving crude oil shipments since the beginning of the year.”36

On one hand, the railroads can point correctly to a very good overall safety record – the American Association of Railroads boasts a 99.997 percent hazmat safe delivery rate. As the use of existing rail lines expands to move more oil, however, the chance of accidents necessarily increases. As one commenter put it, “The rail lines in North Dakota were not built for this kind of traffic.”37

Canada’s Prime Minister has touted Keystone as an environmentally superior (and cheaper) alternative to shipping oil by rail.38 Rail proponents argue that oil shipments by rail have less of an impact on the environment. To the extent proponents of domestic and Canadian oil are correct that, Keystone or not, their product will be sold somewhere, policy makers and even environmental advocates would benefit from considering whether shipments by rail might be more or less environmentally benign than shipments by pipeline.

Also largely undiscussed in the popular press are the ambitious plans of another Canadian pipeline company, Enbridge, to expand the capacity of its existing network. In 2009 Enbridge completed construction of its Southern Access Pipeline, bringing 400,000 barrels per day of crude oil from Alberta’s tar sands deposits to U.S. refineries around Chicago. With additional pumping stations, Enbridge states that it will be able to transport 1.2 million barrels daily. And its Alberta Clipper line, finished in 2010, moves 450,000 barrels a day to the U.S., but can be expanded to transport 800,000. To put this in perspective, the expansion of capacity on these two Enbridge facilities is more than the entire 800,000 capacity of the Keystone XL pipeline.39 These expansions, together with the expanded transportation of oil by rail would render the debate about whether to authorize Keystone academic.

Water Use: A Wildcard

Coal-and gas-fired power plants produce CO2, the latter significantly less than the former. Nuclear power plants produce no carbon emissions. But all of them produce power through a thermoelectric process – they all use steam heat to run turbines. And they use more water to cool the plants. Lots of it. So while the proponents of natural gas and nuclear power are right to tout the advantages they possess over coal as a source of carbon emissions, policymakers would be remiss to ignore the long-term implications of expanded thermoelectric power sources to produce electricity on our water resources.

Writing in the Energy Law Journal several years ago, Prof.Benjamin Sovacool noted that the operations of thermoelectric plants in virtually every region of the country have had to be suspended or curtailed and that water use permits for still others have been denied outright because “they would deplete much needed freshwater for drinking and irrigation.” 40 Between 1950 and 2000, he added, water use associated with conventional thermoelectric power plants increased fivefold. His point is that a shortage of water, not necessarily a concern about climate change, would drive utilities to replace thermoelectric power plants with renewable resources and increased conservation efforts. It’s a point that’s hard to dismiss out of hand. The Department of Energy estimates that 60 percent of existing coal-fired power plants are located in regions of “water stress.” Indeed, its July 11, 2013 report – U.S. Energy Sector Vulnerabilities to Climate Change and Extreme Weather – warns that higher temperatures associated with global warming will only exacerbate the already serious water usage problem.41 Utilities, consumers and regulators are increasingly likely to take the water factor into account.

It’s All Good – and Bad

The notion that the United States can’t achieve either energy independence or effectively combat climate change without an all-of-the-above strategy is hardly novel. It embraces the proposition that America should pursue not only expansion of renewable energy production, but encourage conservation, energy efficiency, clean coal, nuclear power, electric storage, and natural gas exploration. But a little of this and a little of that isn’t an energy strategy. All-of-the-above is valuable only as a conclusion drawn from examining the interrelationship between various energy independence and climate change strategies – their short- and long-term impacts and both their political and economic feasibility. Whether, and if so, how and how much to subsidize one approach will invariably affect the success of other approaches.42

Shale gas can make us energy independent. It can reduce carbon emissions by replacing coal and oil. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t foster renewables. After all, fossil fuel sources are finite and we’ll eventually need to rely on non-carbon based energy sources.

Wind is carbon-free, yet hasn’t increased its market penetration without RPS, tax credits, or other direct and indirect subsidies. But that doesn’t mean we should subsidize it at the expense of other renewable resources. Renewables, on the other hand, generally can reduce our carbon footprint, but if we subsidize them without caution, we may retard conservation efforts or improvements in energy efficiency. Coal is uneconomic compared to natural gas, is dirtier and produces higher CO2 emissions, and carbon capture requirements would make it even less competitive with natural gas. But should we abandon efforts to find economic means to capture and store CO2 and make coal clean because the payoff is far down the road and costly to pursue? Will water shortages impede the development of carbon capture technologies – which require water “to strip CO2 from the flue gas?”43 Nuclear power, too, can reduce carbon emissions, but is there a politically palatable solution to the waste storage problem that would allow greater reliance on nuclear power? And if the waste storage problem is solved, is there enough water available to support significant expansion of nuclear generation? Policymakers and industry participants interested in making the right decisions will grapple with all of these difficult questions.

Endnotes:

1. William D. Nordhaus, A Question of Balance: Weighing the Options on Global Warming Policies, Yale University Press 2008, Chapter 1.

2. Advocates for US energy independence, for example, frequently argue for improving energy efficiency and increased energy conservation as means to reduce reliance on imported fossil fuels. See, e.g., “A National Strategy for Energy Security” (2012), www.secureenergy.org, (accessed July 5, 2013). They’ve also advocated electrification of our transportation networks. Ronald E. Minsk, Sam P. Ori and Sabrina Howell, “Plugging Cars into the Grid: Why the Government Should Make a Choice,” 30 Energy L. J. 317 (2009).

3. Twenty-nine states and the District of Columbia have adopted some form of renewable portfolio standard. Warren Leon, “The State of State Renewable Portfolio Standards,” p.1, CleanEnergy States Alliance, www.cleanenergystates.org, accessed July 23, 2013. The European Union has had a renewable portfolio standard since 2001.

4. California Senate Bill 2 (2011).

5. LCFC Cal. Code Regs. Tit. 17 § 95380. This, some out of state power producers have argued, not only raises questions of unfairness, but may violate the Constitution’s Commerce and Supremacy clauses. SeeRocky Mountain Farmers Union v. Goldstene, 719 F.Supp. 2d 1170 (E.D. Calif. 2010); Pacific Gas & Electric Co., 137 FERC ¶ 61,192 at P22 (2011); Joint Response of the Alliance for Retail Energy Markets and Retail Energy Supply Association in Support of Application for Rehearing of Cowlitz County PUD before the California Public Utilities Commission, Decision No. D11-12-052 (February 6, 2012). But also see Rocky Mountain Farmers Union v. Corey, No. 12-15131 (9th Cir. Sept. 18, 2013) (2-1 decision rejecting claim of facial Commerce Clause violation).

6. See David Coen, “Should Large Hydroelectric Plants be Treated as Renewable Resources, 32 Energy L.J. 541 (2011); Mary G. Powell, “Treatment of Large Hydropower as a Renewable Resource,” 32 Energy L.J. 553 (2011).

7. See, e.g., William D. Nordhaus, “Dealing with Climate Change:What Are the Major Options? (November 2008), www.eba-net.org (accessed July 5, 2013); William G. Gale, “Carbon Taxes as Part of the Fiscal Solution,” Brookings Institute, March, 2013.

8. See, e.g., Kate Ackley, “K Street Files: Manufacturers, Citing Job Losses, Opposed Carbon Tax,” Roll Call, Feb. 26, 2013.

9. See Karen Palmer and Dallas Burtraw, “Cost Effectiveness of Renewable

Electricity Policies,” Resources for the Future, January 2005.

10. Eric Pooley, “Why the Climate Bill Failed,” Time, June 9, 2008.

11. Massachusetts v EPA, 549 U.S. 497 (2007)

12. Evan Lehman and Christa Marshall, “Obama’s Climate Plan will Limit

Emissions from Power Plants and Heavy Trucks,” Scientific American, June 25, 2013.

13. David Boonin, “A Rate Design to Encourage Energy Efficiency and Reduce Revenue Requirements,” National Regulatory Research Institute ( July 2008), http://nrri.org, accessed July 8, 2013. The National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissioners defines decoupling as “a rate adjustment mechanism that separates (decouples) an electric or gas utility’s fixed cost recovery from the amount of electricity or gas it sells.” “Decoupling for Electric and Gas Utilities: Frequently Asked Questions,” 2007, www.naruc.org, accessed July 8, 2013.

14. Richard Sedano, “Decoupling Utility Sales from Revenues,” Report for

the Kentucky Public Service Commission, Regulatory Assistance Project, April 2009.

15. Aaron C. Davis, “O’Malley wins three-year battle over subsidy for offshore wind industry,” Washington Post, March 9, 2013. http://www.washingtonpost.com/local/md-politics/omalley-wins-three-year-..., Washington Post, March 9, 2013.

16. This is the theory discussed in a February 2013 study by the Brattle Group. Jurgen Weiss, Mark Sarro and Mark Berkman, “A Learning Investment-based Analysis of the Economic Potential for Offshore Wind: The Case of the United States,” www.brattlegroup.com (accessed July 13, 2013).

17. Peter Behr, “Battle Lines Harden Over New Transmission Policy for Renewables,” New York Times, Feb. 26, 2010, www.nytimes.com (accessed July 13, 2013).

18. FERC Order No. 1000, FERC Stats. & Regs. ¶ 31,323 at P 400 (2011), (appeals pending), South Carolina Public Service Authority, et al. v. FERC, Nos 12-1232 et al (D. C. Cir).

19. Earlier this year Congress extended the Production and Incentive tax credits to wind power producers. Without these breaks, many have argued that construction of new wind projects would slow to a trickle, supported only by RPS requirements in various states. “Blown Away: Wind Power is doing well, but it still relies on irregular and short-term subsidies,” The Economist, June 8, 2013.

20. Tim McDonnell, “Top 4 Reasons the US Still Doesn’t Have a Single Offshore Wind Turbine,” Climate Desk, February 28, 2013.

21. Policy Statement, Promoting Transmission Investment Through Pricing Reform, 141 FERC ¶ 61,129 (2012).

22. The Conservation Law Foundation, Climate + Energy Project, Earthjustice, Natural Resources Defense Council and Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal Campaign all joined in a July 12, 2013 letter from industrial electric users, municipal utilities, rural electric cooperatives and various state consumer advocate offices addressed to FERC and filed in FERC Docket No. RM13-18, Petition of WIRES for Statement of Policy and June 2013 Edison Electric Institute Report on Transmission Rates of Return on Equity.

23. Henry D. Jacoby, Francis M. O’Sullivan and Sergey Paltsev, “The Influence of Shale Gas on U.S. Energy and Environmental Policy,” Economics of Energy & Environmental Policy, Vol. 1 at 37-51 (2012)

24. Vicki Ekstrom, “A Shale Gas Revolution?” MIT News, Jan. 3, 2012.

26. Mason Inman, “Shale gas has transformed the U.S. Energy Landscape in the past several years—but may crowd out renewable energy and other ways of cutting greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, a new study warns,” National Geographic News, Jan. 17, 2012.

28. Andrew Mayeda and Theophilos Argitis, “Harper Seeks to Build Keystone XL Support on U.S. Visit,” www.bloomberg.com (accessed July 8, 2013).

29. Tennile Tracy, “Pipeline vs. Train Safety in Focus After Quebec Incident,” Wall Street Journal, July 8, 2013.

30. Mayeda and Argitis, supra; Cameron Jeffries, “Unconventional Bridges over Troubled Water – Lessons to Be Learned from the Canadian Oil Sands as the United States Moves to Develop the Natural Gas of the Marcellus Shale Play,” 33 Energy L.J. 75 (2012).

31. “The answer is there’s no safe way to move this oil around,” said Eddie Scher, spokesman for the Sierra Club. “What we need to do is to get the hell off oil.” Stephen Mufson, “Canadian train disaster sharpens debate on oil transportation,” Washington Post, July 8, 2013.

32. “The Experts: How the U.S. Oil Boom Will Change the Markets and Geopolitics,” Wall Street Journal, March 27, 2013.

33. This is the same argument being made by the Canadian government and Canadian crude oil producers. Mayeda and Argitis, supra.

34. Crude by Rail, www.railcan.ca (accessed July 8, 2013)

35. Tennile Tracy, “Pipeline v. Train Safety in Focus After Quebec Accident,” Wall Street Journal, July 8, 2013.

36. Rob Gilles and Charmaine Noronha, “40 Still Missing in Deadly Canada Oil Train Crash,” (AP July 8, 2013)

37. Rusty Braziel, “Ridin the Bakken Slow Rail,” RBN Energy, February 1, 2012, www.rbnenergy.com (accessed July 14, 2012).

38. Mayeda and Argitis, supra, n. 16; “Rail Weighed Against Keystone XL,” May 17, 2013 (UPI) (www.upi.com) accessed July 8, 2013.

39. Lisa Song, “Canadian energy giant Enbridge is quietly building a 5,000-mile network of new and expanded pipelines that would achieve the same goal as the Keystone,” InsideClimate News, June 3, 2013, www.insideclimatenews.org (accessed July 14, 2013).

40. Benjamin Sovacool, “Running On Empty: The Electricity-Water Nexus And The U.S. Electric Utility Sector,” 30 Energy L. J. 11, 12 (2009).

41. “U.S. Energy Sector Vulnerabilities to Climate Change and Extreme Weather,” Department of Energy, July 11, 2013, p. 24.

42. The Treasury Department recently asked the National Academy of Sciences to look at one aspect of the issue, the conflicting impacts of various tax policies on greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The study found that the aggregate effect of existing oil and gas depletion allowances, home efficiency tax credits, nuclear decommissioning tax preferences and production tax credits for renewable energy on GHG emissions, though difficult to measure, has largely been a wash. William D. Nordhaus, Stephen A. Merrill and Paul T. Beaton, “Effects of U.S. Tax Policy on Greenhouse Gas Emissions,” National Research Council 2013.

Category (Actual):

Sound and Fury

How NIPSCO feels leaned on.

Bruce W. Radford is publisher of Public Utilities Fortnightly. Contact him at radford@pur.com.

Northern Indiana Public Service, the MISO member sandwiched between PJM’s Ohio territory and its noncontiguous Chicago outpost, feels particularly aggrieved by the failure of the MISO-PJM Joint Operating Agreement, approved by FERC in 2004, to facilitate cross-border grid projects to relieve constraints along the ragged and interlaced seam that separates the two regions.

In a complaint filed at FERC just last month, NIPSCO asked for relief from the omnipresent PJM power transfers across the gap between Ohio (in MISO) and Chicago (in PJM). These power flows lean on NIPSCO transmission lines, sometimes even forcing some of those lines to be opened, raising concerns over N-2 contingencies.

“That nothing has been built,” says NIPSCO, “is not due to lack of need.” (Complaint of No. Ind. Pub. Serv., FERC Dkt. EL13-88, filed Sept. 11, 2013.)

The need – for more transfer capability linking Ohio and Chicago – stems from PJM. But meeting that need means building lines within MISO. It’s the classic case of a cross-border problem that FERC had in mind when it added the interregional provisions to Order 1000.

The MISO-PJM JOA was supposed to solve such constraints, yet the odds appear stacked against any progress.

As NIPSCO explains, even if MISO were to identify a possible cross-border market efficiency grid project (MEP) in its own 2014 regional plan that would aid both regions, the project likely wouldn’t emerge from the JOA study process until 2015, and then would have to pass PJM’s own two-year intra-regional planning process, which wouldn’t be finished until the end of 2017. And that’s assuming no iterative modifications along the way, which would send everything back to the drawing board.

Says NIPSCO: “For the RTOs to cite the JOA as a ‘model of coordination’ … is unfounded in actual practice.”

“The process,” it adds, citing Shakespeare, “has been ‘full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.’”

For more information, see "Cross-Border Bargaining."

Department:

Don't Fear the FERC

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s enforcement of its anti-manipulation regulations has resulted in numerous actions with significant civil penalties and disgorgements of profits. While cases such as those involving Constellation, Barclays, and JPMorgan grab the news headlines, many other entities have settled investigations with FERC for multi-million dollar amounts that, although smaller by comparison, can still cause a significant hit to a company’s bottom line.

All companies engaging in energy trading – whether large or small, and whether directly regulated by FERC or not – must be mindful of this growing area of enforcement and should undertake actions to minimize enforcement risk. Many companies will, rightfully, view the risk of FERC enforcement proceedings as minimal, particularly if the company believes it runs a fully compliant operation. FERC, however, investigates many matters that ultimately do not result in civil penalties. Companies must thus be prepared to support and defend their actions even if they have done nothing wrong. In addition, because this enforcement program is its relative infancy and has not been meaningfully tested in the courts, it cannot be understated that there are few bright lines that distinguish creative and aggressive trading from market manipulation.

In this regard, companies can undertake several straightforward yet effective steps to minimize the likelihood of an investigation and reduce the risk of an adverse outcome in the end. Any of these suggestions, however, should be discussed with counsel before implementation.

Rule 1– An Ounce of Prevention Is Worth Many Pounds of Cure

FERC has stated that companies should maintain a “culture of compliance.” To most, this means that executives must lead by example and instill appropriate values in their employees. But more is required than published codes of conduct and statements of executives to instill fully a culture of compliance. In this regard, an ounce of prevention in instilling a true culture of compliance is worth many pounds of cure. But instilling a true culture of compliance requires more than just management say-so. It requires substantive training, management presence, and willingness of the company to undertake potentially unpopular actions (including appropriate disciplinary actions) when necessary to ensure compliance.

One effective means of instilling a culture of compliance is regular, substantive, and meaningful training of employees with regards to compliance matters. Each session need not be extensive. Indeed, employees often learn better in shorter increments rather than in day-long sessions. Most companies have regular department meetings and brief compliance training sessions. These gatherings can be used as a place to reinforce the “culture of compliance” message and convey important information in a timely manner. Certain lessons likely warrant repeating at these sessions (e.g.,“Routinely losing money on one type of transaction will likely raise FERC’s eyebrows, so keep a close eye on your P&L”), but the balance of the discussion should change subject regularly, and focus on new developments when they happen, in order to keep people’s attention. Training is critical because many energy traders come from backgrounds outside the regulated world of wholesale power and have little to no exposure to FERC.

Executive or senior management attendance and involvement at such training can be valuable as well. Not only does it reinforce that the culture of compliance comes from the top, but it provides a forum for employees to express concerns and ideas, and for management to provide guidance that is consistent with the overall goals and practices of the company. In this vein, while many companies have “compliance hotlines” to report concerns to management, some have also adopted “no retaliation” policies to further encourage reporting. It may be appropriate, however, to limit any such policies so that deliberate or reckless acts have real adverse consequences for the people involved.

Rule 2– Be Present, Be Vigilant, Be Proactive

Management proclamations and training in the culture of compliance can only go so far. People forget things and “when the cat is away, the mice [often] will play.” Sometimes the best defense is a good offense, which, in the enforcement context, means oversight and proactive efforts to identify problems.

Out of sight means out of mind. While a poster stating a company’s code of conduct is a useful reminder, it is no substitute for compliance personnel being present. Their presence not only reminds employees that their actions will be scrutinized, but, on a more positive note, it provides employees an easy opportunity to ask questions. This two-way communication is critical to establishing an effective compliance program. Where compliance personnel come from the in-house legal team, management may want them to sit in the legal department. But management should also consider giving them a second office, or perhaps even better, a desk on the trading floor so that they can spend part of their time shoulder-to-shoulder with traders.

Presence means little, however, if personnel – traders and management alike – are not vigilant. Everyone must keep open eyes and ears toward what is happening. Willful ignorance might seem inviting, but it is unlikely to serve a company well in the long term. Questions should be asked, but without accusation. Traders should understand that this is not an indictment but merely part of the process of ensuring compliance. If management or other traders have questions about certain actions, FERC will likely as well. It is better to understand the actions sooner rather than later.

Vigilance often involves proactive efforts by companies. Management should not wait for employees or FERC to identify concerns. Often, that will come too late and well after questionable conduct has occurred. Further, employees might not have access to the information about other employees needed to connect the dots and identify an issue. Management will have the data and should mine it for issues. While most companies investigate outsized losses, they should also investigate outsized wins to ensure that they were attained in a compliant manner. If companies record IMs or other communications, they might also want to spot check them or search for words that could raise compliance concerns.

Rule 3– Document Thoroughly and Thoughtfully

A paper trail often can be the best defense in the face of an investigation. Actions and reasons for actions are often forgotten with time, and FERC may ask questions many months or even years after trades took place. In the rapid world of trading, memories can get fuzzy quickly and employees who hold key information can leave. Documenting events as they occur can be useful in answering regulators’ questions.

While documenting can be helpful in the long run, it can also be a double-edged sword. However, having no document policy is unlikely to help anyone. While there is no one-size-fits-all policy, merely having a document policy may be the most important step. The advice of counsel with regard to the development of a document policy is critical, particularly as to the best means to preserving attorney-client privilege, where available.

One area of documentation that should not be controversial, however, is the need to keep business records – including trading data – in an orderly manner. Sloppy recordkeeping might be perceived as general sloppiness and a lack of attention to compliance obligations.

Rule 4– Know Thy Regulator

A regulator’s job is to enforce the law. Companies and employees must understand and respect that fact. The regulator’s job includes looking at actions skeptically. Arguing with a police officer who asked “why were you speeding” accomplishes little. Getting defensive with regulators looking into trading activities accomplishes little as well (and might make regulators think there is something to hide). Be prepared to defend actions, but do not get defensive.

Companies should look at their own trading activities with a skeptical eye as well. Ask “How would this look to FERC if viewed in the worst way possible?” Certain perfectly compliant transactions might look inappropriate under certain circumstances or if only some of the data is seen. Defending an investigation into perfectly legal action can be costly even if the action is dismissed. Thus it may be better to avoid activities that, although legal, might appear to the regulator to be problematic and result in an investigation.

The body of law surrounding FERC enforcement of energy trading is still in its infancy as compared to that of other federal agencies. As a result, almost every FERC enforcement order provides useful study. While some issuances might seem to be “more of the same,” there are often subtleties that can indicate how FERC’s thinking and policies are evolving. Companies should, of course, stay knowledgeable about the facts underlying new orders but should also look for these subtleties as they can be invaluable in understanding FERC and avoiding, or shortening, investigations.

While there is no one-size-fits-all for a compliance program, certain common elements exist among many effective compliance programs – the need for a true culture of compliance, active oversight of trading operations, a balance documentation policy, and an understanding of regulators’ policies. Even the best compliance program is no guarantee against an investigation, but it will likely minimize the likelihood of the investigation and any adverse consequences stemming from it.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jeffrey M. Jakubiak (Jeffrey.Jakubiak@troutmansanders.com) is a partner in the New York City and Washington, DC offices of Troutman Sanders LLP. His practice focuses on FERC regulation of energy trading and electric-asset transactions. This article does not constitute legal advice nor does it establish an attorney-client relationship between the author and the reader. The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect of the views of Troutman Sanders LLP or its clients.

Anomaly or New Normal?

Regulators weigh interest rate climate and future Fed policy in setting allowed return on equity.

Phillip S. Cross is Fortnightly’s legal editor, and serves on the editorial staff of PUR’s Utility Regulatory News, reporting weekly on state ratemaking and regulatory decisions.

By the term “anomaly,” we don’t mean “Armageddon.” With the government shutdown recently lifted as this issue was going to press, we offer no prediction on how the continued sense of budget uncertainty and risk of future U.S. credit default might affect utility rate making and cost recovery.

Rather, this year’s annual survey of retail rate case orders and the rates of return on common equity (ROE) authorized therein prompts a question much less worrisome, though no less urgent:

Should the historically low interest rates of the past several years require a haircut to the ROEs authorized for regulated electric and natural gas distribution utilities in rate cases now being decided, or does this credit climate represent an historical anomaly – one that should call into question whether today’s rate-making methods, which for years have remained largely unchanged, are still producing the right answers?

Here, as in every survey, we provide data from all major electric and natural gas rate case orders. But we also take a look at three new rate case opinions from the past year that address the question of Anomaly vs. Normal: one from Connecticut, one from Alabama, and one from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC).

Rate-Making Methods

Over the past several years, the Fortnightly’s annual November rate case survey has revealed a continued reliance on the discounted cash flow (DCF) model as the touchstone for ROE determinations. Other methodologies are considered, however, and in the end most commissions inform us that the process is as much art as science, with the goal being to balance the evidence and apply sound judgment to produce a fair rate of return.

Wrangling over technical aspects of financial modeling comprises the lion’s share of the record, but the essential question remains the same: what figure will give the utility a fair chance to attract equity capital?

Under traditional rate-base and rate-of-return regulation, investors are thought entitled to earn a return that falls within a “zone of reasonableness.” And as further defined by federal and state courts, a fair rate is one that is sufficient to attract capital on reasonable terms and high enough to enable the utility to maintain its financial integrity.

One way regulators have approached the question is to begin by looking at how much an investor would earn by purchasing a so-called risk free investment, generally measured as the interest rate on U.S. Treasury bills. Rates for these instruments have remained low for several years, and encouraged to stay low by a Federal Reserve dedicated to easing credit and boosting the economy.

This climate has led those seeking higher ROE awards to argue that the current interest rate trend is anomalous – that recent indications suggest the Fed will soon rework these near-zero coupon rates and ratchet them upwards, possibly to tamp down any inflationary pressures as the economy begins to recover from the Great Recession.

Three August Viewpoints

In August, in a widely watched case, FERC Administrative Law Judge Michael Cianci chose to ignore claims that the current interest rate climate

climate is somehow anomalous.

He rejected expressly any argument that “these unusual financial and economic times” must render the traditional ROE analysis obsolete, but conceded that on appeal the full commission would be “free to consider any policy decisions it believes are warranted.” Martha Coakley v. Bangor Hydro-Elec. Co. et al., Docket No. EL11-66-001, Aug. 6, 2013, 144 FERC ¶63,012, at ¶549.

The judge ruled that FERC precedent required strict adherence to results of the DCF method of financial modeling in setting the base ROE. That finding led the judge to rule that the current 11.4-percent base-level ROE (shorn of all incentive adders) that has long applied to network transmission service provided by ISO New England across the six-state region over lines owned by New England’s electric transmission owners (NETO) is unreasonable and unlawful under existing capital market conditions – i.e., declining yields for Treasury and public utility bonds. (For more detail on the case, see “Investor Sequester,” this column, June 2013, http://www.fortnightly.com/fortnightly/2013/06/investor-sequester.)

But if lower ROEs are indeed the new normal, what might we expect in terms of utility growth?

Often, claims on whether a rate is high enough to attract and hold investors over the long term are simply left to stand on their own. Or, they are sometimes buttressed only by statements regarding the effect on future credit ratings an ROE award might make. Accordingly, it’s interesting to note that Judge Cianci in the FERC proceeding assigned “moderate probative value” (144 FERC ¶63,012 at ¶576) to a study purporting to show that if ROE is set substantially below 10 percent for long periods of time it could negatively affect future investment in NETOs.

On the other hand, Fortnightly Editor Michael Burr reported in last month’s issue that regulated utilities succeeded in raising near-historic amounts of debt capital during the period since 2008, with such success attributed at least in part to favorable regulatory treatment at the state level. (See, “Five Years Later,” October 2013.)

In another case handed down in August, involving United Illuminating, the Connecticut Public Utilities Regulatory Authority (PURA) also reviewed conflicting arguments on whether historically low Treasury bond rates would remain, or would be pushed higher soon by evolving Fed policy. Connecticut decided, for the most part, that low interest rates would continue for the foreseeable future, justifying an authorized ROE of 9.15 percent – up from the prior rate of 8.75 percent, but lower than UI’s request of 10.25 percent. (United Illum. Co., Conn.PURA Docket No. 13-01-19, Aug. 14, 2013.)

In other words, the lesson from Connecticut was mixed.

On one hand, the PURA warned us not to assume that continued low interest rates would guarantee the company’s continued positive financial performance. Such “presupposition is inappropriate,” it noted. Yet the PURA sided with the state’s Office of Consumer Advocate that achieving a 6.5-percent national unemployment rate – a benchmark that could trigger a new, less expansive monetary policy from the Fed – appeared unlikely in the near future.

A somewhat contrary view comes from the Alabama Public Service Commission in a third decision issued in August. In a case involving Alabama Power, the PSC rejected allegations that current economic conditions (i.e., low interest rates) indicate reduced expectations by utility stock investors. (Alabama Pwr. Co., Ala.PSC Docket Nos. 18117, 18415, Aug. 21 2013.)

The PSC rejected claims that the utility’s then-current authorized ROE range of 13 to 14 percent was too high given the persistently low interest rates seen in the market. It rejected a 10-percent compromise ROE that was proposed by consumer advocates and based on traditional analyses using the DCF and CAPM (capital asset pricing model) methods.

Instead, the PSC found the current low interest rate climate anomalous, as argued by the utility.

The commission added that while a consumer advocate witness had noted a downward trend in allowed returns, he had neglected to acknowledge an offsetting increase in common equity ratios among utilities over the same period.

As the PSC noted, the consumer advocate’s argument was based in part on “an unsubstantiated conclusion that the current environment of ‘artificially low’ interest rates represents normal conditions for the foreseeable future.”

Download Figure 1: 2013 Rate Case Study in pdf format here.

Notes to the figure:

* Settlement agreement ROE not specified.

NA = not available

1. Utility operates under a rate stabilization and equalization plan – an alternative rate-making mechanism that provides for periodic automatic adjustments to rates to maintain ROE within a specified range.

2. Equity ratio capped at 55 percent. Down from 60 percent per order dated 12/01/2009.